One of eight siblings born into poverty near the Wicker, Sheffield, Harry Brearley (1871-1948) could be considered an unlikely individual to make a revolutionary metallurgic discovery. At the age of twelve he was taken on as a ‘cellar boy’ at Thomas Firth & Sons: the same crucible steel works that employed his father, whom Harry described as “an expert steel smelter and an expert ale supper” (Sephton, 1999: 30). In his own words, Harry was awarded this position simply due to the fact that his “face was cleaner than another’s” (ibid.). Latterly Harry was promoted to the position of ‘bottle washer’ in the firm’s chemical laboratories where he was greatly impressed by a chemist, James Talyor, who had become a night school student and won a Whitworth scholarship in the face of appalling poverty and difficulties. Harry also clearly impressed his employers, because soon after being transferred he was awarded the post of laboratory ‘general assistant’ and by his early twenties the firm had apprenticed him as a ‘laboratory assistant’. For several years, in addition to his laboratory work, he studied at home and took evening classes in steel production and associated chemical analysis methods.

By his early thirties Harry had earned an independent reputation as an experienced professional, astute in the resolution of practical and industrial metallurgical problems. In 1901 he briefly left Thomas Firth & Sons to start a new laboratory at Kayser Ellison & Co. steel works, which was also based in Sheffield, but in 1903 he returned to the firm spending three years experimenting with different ideas for steel composition as the works manager of its steel plant in Riga, Russia. In 1907 Harry returned to Sheffield to take charge of the newly established Firth & Brown Research Laboratories (following the merger Thomas Firth & Sons and John Brown & Co., which became ‘Firth Brown Steels’). In 1912 the Firth & Brown Research Laboratories were commissioned to study rifle barrel metal erosion by a small arms manufacturer who wished to prolong the life of its guns, which were eroding too quickly due to the action of heating and discharge gasses. In response Harry set out to discover an erosion resistant steel, not a corrosion resistant one, and began experimenting with steel alloys containing chromium, because these were known to have a higher melting point than ordinary steels. He experimented with several variations of steel alloy, ranging from 6 per cent to 15 per cent chromium with different measures of carbon. In order to gauge the wear resistance of the alloy samples, he etched each with acid and examined the effect on the grain structure of the steel under microscope.

On the 13th August 1913 Harry created a steel alloy with 12.8% chromium and 0.24% carbon, which is argued to be the first* ever batch of what became known as ‘stainless steel’. The etching re-agents he used were based on nitric acid and he discovered that this new steel strongly resisted acid attack. However, his employers, Firth Brown Steels, were not interested in the armament potential of this new alloy, which Harry called ‘rustless steel’. Therefore, he suggested alternative uses, in particular the utility of such an alloy to Sheffield’s Cutlery Industry. Harry had exposed samples of his rustless steel to vinegar and other food acids such as lemon juice, and found that it resisted attack from all such substances. At that time the majority of cutlery was either constructed of carbon steel, which had to be thoroughly washed and dried after use, and even then rust stains would have to be rubbed off regularly using carborundum stones. Or, it was plated with nickel or silver, which would eventually wear through to the base alloy. However, his suggestion that rustless steel would be an excellent material for cutlery production was publically ignored, although privately Firth’s are known to have sent two samples to Sheffield cutlers for their opinions. They reported back that the alloy was useless due to difficulties in forging, grinding and hardening. However, these cutlers took no instruction from Harry regarding the correct temperatures or specifications to produce rustless steel wares and declared both batches a failure. The talk of the town was that Harry Brearley was “the man who invented knives that won’t cut” (ibid.).

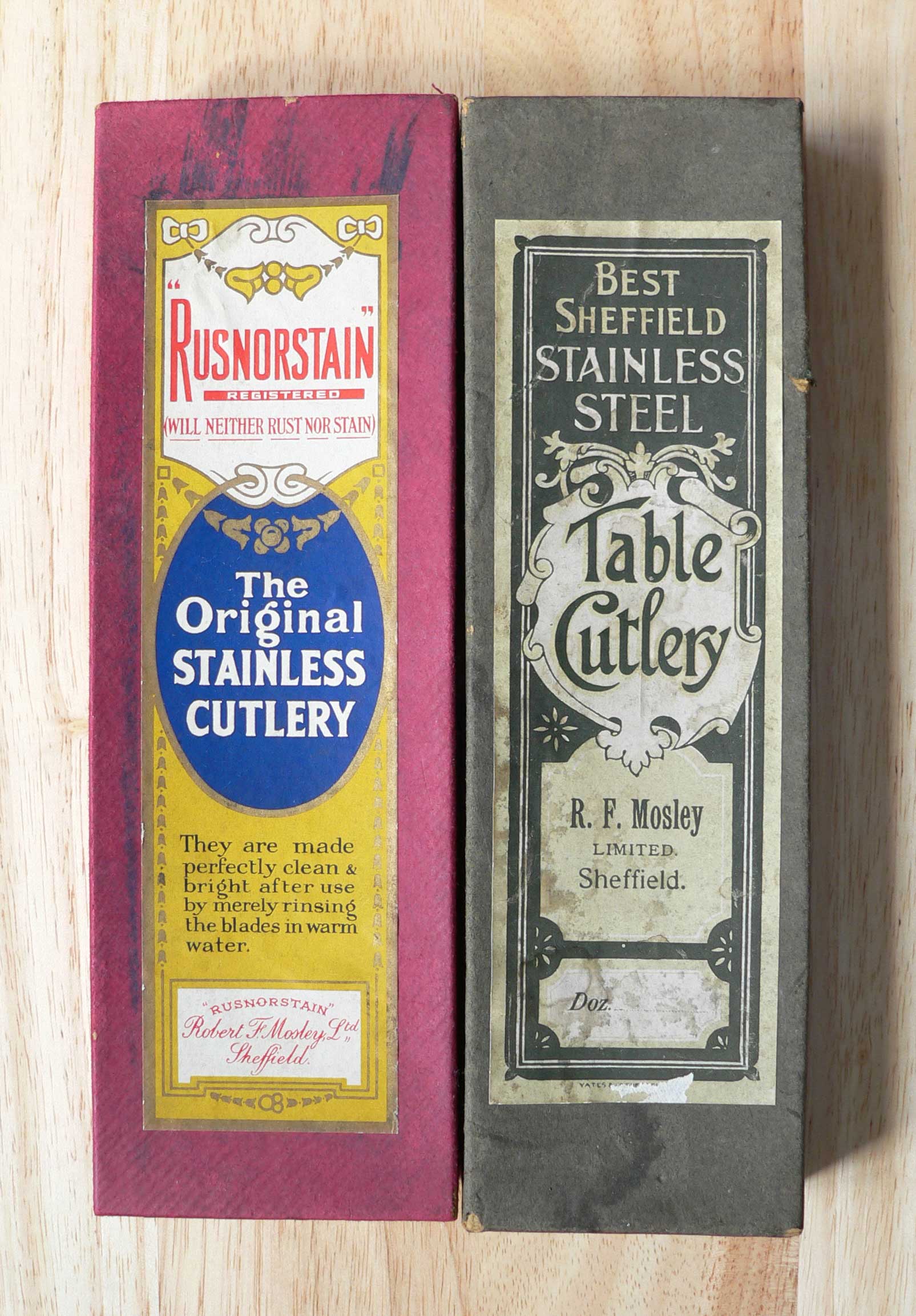

However, being a man of considerable conviction Harry was unperturbed by this setback. Through an intermediary he purchased one hundred weight of chromium steel from his employer and arranged for it to be made under his own careful supervision into rustless steel cutlery by a local cutlery firm: R.F. Mosley & Co. of Portland Works, Randall Street. Working closely with the cutlery manager of R.F. Mosley & Co., Ernest Stuart, who recognised that rustless cutlery could be of considerable merit, Harry supervised the production of a number of batches of cutlery, which he gave to his friends, asking them to return them “if fruit, condiment or food marks them” (ibid.). None were returned. In the process of testing the corrosion resistance of Harry’s new steel alloy with vinegar for himself, Ernst Stuart commented that stainless steel would be a more marketable name than rustless steel. Thus, ‘stainless steel’ was born in Portland Works! Harry returned to his employer adamant that this kind of steel had enormous potential. However, the conservative directors at Firth & Brown Steels proclaimed that “restlessness was not so great a virtue in cutlery, which of necessity must be cleaned after each using”, and so he was again ignored to the point of reprimand for being over enthusiastic (Mittal Corp Ltd., 2010).

Later that year, shortly before the outbreak of the First World War, a Firth’s director visited the factory of Krupps and Co. in Essen, Germany. On the desk of one of the company’s directors he saw a bar of shining steel. The man who had seen nothing unique in Brearley’s work suddenly realised the consequences too late. Firth Brown Steels had no patent, nor were they aware of the properties that would give rise to patent rights. The Germans had beaten them to it, which would not have been the case had they listened to Harry Brearley and his views on stainless steel. Harry resigned from the Firth & Brown Research Laboratories in dispute over ownership rights of the invention of stainless steel in 1915, which the company claimed full ownership of due to the fact that he was an employee. Harry became works manager at Brown Bayley’s Steel Works in Sheffield, where he continued with the development and production of stainless steel. However, later that year a 75-year old man from London, who had read of Harry’s work and frustration, approached him with a proposition. This individual believed that stainless steel represented a huge opportunity in the U.S.A., where no patent had yet been registered. He and Harry duly obtained the US patent, but they required assistance to develop the product across the Atlantic. Harry reluctantly returned to his former employer and formed a new venture partnership with them, which was named the ‘Firth Brearley Stainless Steel Syndicate’.

In 1921 Harry had to visit the U.S.A. to act as a witness over his patent rights. However, Firth & Brown Steels undermined his case yet again. They insisted that the patent was theirs and continued to argue that he was merely an employee. So he broke his arrangement with them in exasperation. A year earlier, in 1920, Harry was awarded the Iron and Steel Institute’s Bessemer Gold Medal. He eventually became a director of Brown Bayley in 1925. Although he was never awarded ownership of his invention, Harry’s chromium steel formed the basis for the wide range of stainless and special steels, which are now used across the globe. A case in Sheffield’s Cutlers Hall still contains a set of ordinary looking table knife blanks and blades. These knives – produced in Portland Works by R.F. Mosley & Co. and presented to Cutlers Company of Hallamshire by Harry Brearley Esq. – are the earliest specimens of stainless steel cutlery in the world. In his autobiography: ‘Knotted String’, which was published in 1941, Harry commented that his discovery of stainless steel was a:

“Highly coloured incident. The people in authority saw nothing of commercial value and still less of scientific interest in it. The rusting of iron is universally accepted and no one seems willing to accept that it can be overcome. I hope I will not be taken amiss if I say that workmen are often much wiser than their masters” – Brearley, 1941

It is our hope dear reader that the value of Portland Works and its industrious tenants will not be dismissed with the same ignorance today as Harry Brearley’s inventiveness was all those years ago.

References:

Header image courtesy of Picture Sheffield.

2) Sephton P 1999 Walk Sheffield’s Heritage Rotary Club of Sheffield, Sheffield.

3) Mittal Corp Ltd. 2010 The History of Stainless Steel

4) Brearley H 1941 Knotted String: an autobiography of a steelmaker Longmans, Green and co, London.

* Other claims have been made as to who invented stainless steel. However, these were based on published experimental research papers, which merely indicated the potential corrosion resistance of chromium steels. Harry Brearley’s contribution was that, having come to a conclusion by purely empirical means, he immediately seized on the practical uses of this new material.